Urban Renewal in Boston’s South End

Written by Sadie Kennedy

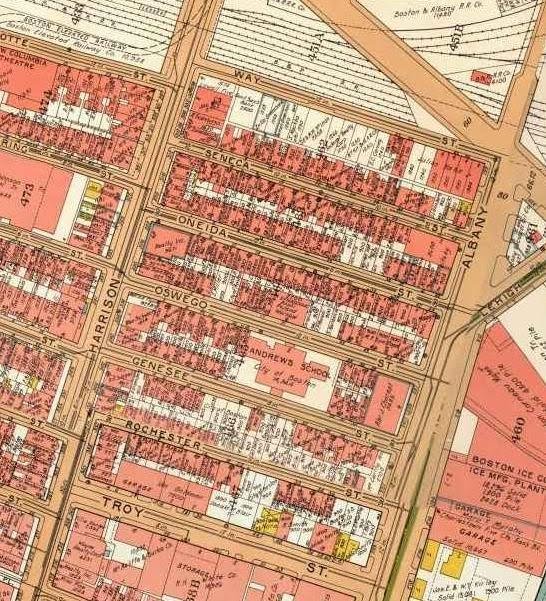

In the fall of 1955, Mayor Hynes ceremoniously removed the first brick from Boston’s “New York Streets,” marking the start of a large-scale redevelopment project (Kneeland, 1). The neighborhood was once alive with kids playing in the streets, and adults chatting on porches (Admin, 1). By the spring, the neighborhood in the South End would be cleared to the ground to make way for new industrial buildings, and ultimately a new era for Boston. The run-down neighborhood, seen by the government as a blight on Boston, presented an opportunity for growth for the economically stagnant city. The project, however, had tragic implications on the South End community.

Many cities in the US experienced discouraging trends during the mid 20th century. The story was the same across the nation: the failure to upkeep buildings and businesses during the Great Depression led to the growth of slums. Eventually, the middle class and wealthy fled outward from cities, leading to the creation of extensive suburbs, while the heart of cities declined(Futterman, 5). Due to this decentralization, Boston lost ⅙ of its population during the 50’s, despite growth in the larger metropolitan area. According to Robert A. Futterman, a real estate developer and investor, “No downtown in America needs quite so much work as Boston”(Futterman, 116).

Boston’s government set the intention to improve the city and revitalize the economy. The Boston Chamber pledged to become more “industrial development minded,” in January, 1955 (Hennessee, 1). Hoping to help turn things around, Congress passed the Housing Act of 1949. Title I promised partial Federal funding for cities to clear and redevelop neighborhoods, a process known as urban renewal (Brennan, 1). Most states, including Massachusetts, incorporated laws to kickstart urban renwal. Urban renewal made it possible for cities to replace neighborhoods that were physically deteriorating. Cities created master plans mapping out areas to target for a beautification process. However, local governments often opted to take the route that would create the best economic or social outcome, and develop high-income housing or commercial buildings, forcing the previous residents to relocate.

Boston saw opportunity for improvement in the New York Streets Neighborhood in the South End, among other, mostly smaller locations. The neighborhood was mostly 4 and 5 story tenement houses. The BCPB, Boston’s urban planning board, recommended in the 1940’s that the best use would be as a low cost residential area, as it always had been, with some additional businesses and parks. They orchestrated studies of Boston’s housing conditions and recommended taking measures to make “conditions of urban life less repellent.” As the decade progressed, the demographics of the South End changed. More African Americans moved into the South End, creating a vibrant community for not only African Americans, but other minority and immigrant groups. By the 1950’s, the neighborhood’s property values dropped more than 50% (Keblinsky, 1). Boston organizations instead suggested more drastic measures to “improve” the South End. The Boston Housing Authority recommended to level and sell the land where the New York Streets Neighborhood stood (Brennan, 1). The location was valued for it’s proximity to Downtown Boston. Boston’s Authorities looked down on the New York Streets Neighborhood as a slum. The BCPB didn’t hid their classist, and likely racist goal to “draw desirable citizens back to the city,” as they put it (Brennan, 1). However, residents did not think view their home as a slum. Mel King was a politician and activist, born in the South End in 1928. Referring to the events that took place in his neighborhood, he said, “Somebody else defined my community in a way that allowed them to justify destruction of it” (Brennan, 1). The city authorities did not take into consideration the opinions of the residents. The residents of the New York Streets had relatively no power compared to the city authorities, and there was little they could do to protect their community against the will of the government.

The injustice that came along with urban renewal seems clearly like a government overreach. Citizens of the United States are guaranteed fundamental rights, including “life, liberty, and property” (U.S. Constitution, amend. 5, sec. 3). Urban renewal’s destructive methods don’t seem to fall in line with the Bill of Rights. However, urban renewal is legal through eminent domain, a power of the United States Government, allowing seizure of private property as long as residents are given fair compensation. Eminent domain, permitted by the 5th amendment, was originally used for public projects such as to clear the way for public buildings, restore parks, and facilitate transportation. With the support of courts, the government began to expand this practice for beautification. The supreme court, in Berman v Parker, 1954, concluded in a unanimous opinion that "If those who govern the District of Columbia decide that the Nation's Capital should be beautiful as well as sanitary, there is nothing in the Fifth Amendment that stands in the way"(Berman, 1). This decision expanded the parameters of eminent domain to allow cities to exercise it for their own agendas. Once the government decides to seize property, citizens have essentially no power. The most they can do is contest in court the price of compensation they were given.

The residents of the New York Streets Neighborhood became victims of urban renewal (Keblinsky, 1). Fifty of the 225 families who occupied the neighborhood right before demolition were moved to public housing projects (Keblinsky, 1).The Federal Government contributed two thirds of the estimated $4,300,000 cost of leveling (City, 1). After all of the residents moved out and the buildings were removed, the Boston Housing Authority advertised the 16 acre site to developers who would build a commercial or Industrial center. In the place of the neighborhood, they constructed a massive new Boston Herald building.

The perceived success of the New York Streets Urban Renewal Project kickstarted other renewal projects throughout Boston, such as the extensive West End Project, which had a budget of $18,000,000. There were several smaller scale urban renewal projects in the South End, such as the Cathedral Housing, Tent city, and Villa Victoria projects. However, some communities didn’t leave without putting up a fight. The “Tent City” redevelopment zone got it’s name from the protest that its resident staged, where they camped out on the site demanding affordable housing. The residents of Villa Victoria, a Puerto Rican Community, protested to have some say in the redevelopment process. Both were successful in gaining some sympathy from the local government, ensuring affordable housing for Tent City, and allowing residents to help design the new homes in Villa Victoria (Admin, 1). Often times, redevelopment took so long, up to multiple decades, so former residents didn’t bother returning. Compensation for their homes was simply a bandaid on a bullet wound. Urban Renewal has more critics today. Although it is not put into practice very often, there are still forces that destroy low-income and minority communities in US cities. Rising housing costs drive people out of their homes, which is what is currently happening in the South End. Just like with Urban Renewal, the tight knit communities are put in jeopardy by gentrification.

Works Cited

“Abolish the BPDA | Michelle Wu for Boston.” Www.michelleforboston.com,

www.michelleforboston.com/plans/abolish-bpda. Accessed 24 Feb. 2023.

Admin. “South End History, Part III: Urban Renewal.” South End Historical Society, 8 Apr.

2012, https://www.southendhistoricalsociety.org/south-end-history-part-iii-urban-renewal

/.

"Berman v. Parker." Oyez, www.oyez.org/cases/1940-1955/348us26.

Bill of Rights (1971). Bill of Rights Institute,https://billofrightsinstitute.org/primary-sources/

Bill-of-rights

“Black History Boston: Mel King.” https://www.boston.gov/news/black-history-boston-mel-king

Brennan, M. J. “The Environmental Roots of Urban Renewal in Boston. Journal of Urban

History,” 2019. https://doi-org.ezproxy.bu.edu/10.1177/0096144217701259

"City Readies Sale of 16-Acre Site for Industries." Daily Boston Globe (1928-1960), Oct 22

1955, p. 10. ProQuest. Web. 4 Feb. 2023.

Futterman, Robert A. TheFuture of Our Cities. Garden City, N.Y., Doubleday, 1961. HeinOnline,

https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.beal/futcites0001&i=305.

Hennessey, Thomas. "Boston Chamber Pushes Industrial Growth: Development Committee

Organizes to Attract New Industries and Keep Old Ones." Daily Boston Globe

(1928-1960), Jan 16 1955, p. 1. ProQuest. Web. 4 Feb. 2023 .

“History of the Federal Use of Eminent Domain.” Justice.gov, 24 Jan. 2022,

www.justice.gov/enrd/history-federal-use-eminent-domain.

Keblinsky, JOSEPH. "Redevelopment of South End to Start Friday." Daily Boston Globe

(1928-1960), Sep 21 1955, p. 1. ProQuest. Web. 4 Feb. 2023 .

Kneeland, Paul. "Corner Stand: ...And The Walls Come Tumbling Down." Daily

Boston Globe (1928-1960), Oct 02 1955, p. 1. ProQuest. Web. 4 Feb. 2023 .